Preached for the Nativity of Our Lord.

The tableau we’ve just heard from the Gospel is rendered in Western art as an Adoration, an arrangement of adoring figures that gets copied again and again in nativity sets in church and at home. In paintings depicting the adoration of the Christ child, the shepherds peer in awe around the corner of a straw hut, while Mary herself hovers above the infant with her hands clasped in awe or prayer. I find this deeply peculiar. Why doesn’t Mary hold the baby? Anyone who has been near enough a newborn knows that you don’t adore an infant by staring at it, you adore him by holding him close in your arms, by trying to discern her crys, by rocking him gently off to sleep. I want to see a nativity where the baby Jesus is being passed lovingly from one shepherd to the next while the travel-weary mother gets a break.

I, myself, had the privilege of holding the baby Jesus for a while last week. I am speaking, of course, of the baby Jesus from our pageant yesterday who was played by our very own Trajan Kingsley. Josh and I were working on a project together and Josh needed a little break of his own from having Trajan strapped to his chest for the past several hours. I gladly took him, and he was not-as-gladly received. He spit up a bit on the shoulder of my hoodie, refused his bottle, but eventually fell asleep in my arms after a bit of swaying and some songs. Every time I hold and rock and sing to baby Trajan I am reminded of how deeply my own fitful soul needs to be coddled this way. Christmas is a great feast for doing this, all it takes is the bass line to Angels we have heard on High and I can feel the crankiest part of me softening into a supple, relaxed stupor. Another friend of Nathan and I whose daughter, Eliena, is even younger is just beginning to push herself up. If her hands are held in just the right way, her arms quiver with the strength she is gaining in the effort to hold her whole self upright. It becomes this kind of dance, holding her hands while her elbows and knees wobble somewhere beneath her -I ease off on the weight I’m bearing so she can learn to bear more and more of herself as she grows.

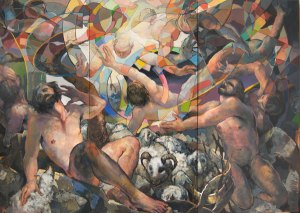

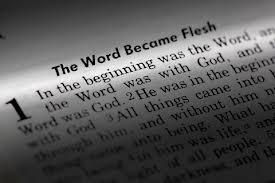

The great mystery and wonderful sacrament of the incarnation is that God comes to us as one needing to be held. The Word of God comes unfinished in a mother’s womb, like a thought searching for just the right way to be uttered. The Word of God comes ready to be born and shaped by the people he will meet, the people who will come to help him on his way through this world and keep him company when he is lonely and afraid. Christ trusts himself to us. Christ lets us tell the story he has come to author in our own words, knowing that we’ll never really get it quite right, knowing our penchant for tall tales and hard lines and too much bloody gore. Christ brings the whole Peace of God down to earth and then leaves it there to be used up, worn out, tattered by carelessness and love and eventually renewed entirely, a patchwork quilt of all the souls who have lent their hands to mend it.

In some version of heaven this God of ours may be adored by clasped hands and hymns sung in perfect harmony across an unsearchable multitude of angelic hosts. But here on earth we adore our God by holding him. We adore our God by trying to listen very carefully to his cries for help, and learning to discern what they mean for the needs of his people. We adore our God by helping his ever newborn body of the Church learn to wobble with the strength we are gaining as we learn to stand upright in the ways of God’s justice and God’s truth. For this is the very thing he does for us, in the flesh, as one among us. Christ coddles our cast down, disquieted souls within by the softest, sweetest song of Himself. His Spirit tends to every cry we make, and props us up just enough to learn to use the strength which we ourselves are gaining. His God draws as near to us as a mother’s arms are to her only child, as near as bread upon our lips, and remains there for all time, as close our own two arms are ready to receive him.